The fascinating life of female cycling trailblazer Elsa Von Blumen

I especially love a story that combines my love of cycling, my fascination with social history, and my interest in the female suffrage movement, so Elsa Von Blumen gets my attention. I have to thank Karen Lankeshofer from Rochester in the US, where Von Blumen hails from, for getting in touch with me to highlight Von Blumen’s achievement.

I wrote a little about Von Blumen many years ago when I came across an excellent book called Wheels of Change by Sue Macy. Von Blumen is one of the women highlighted in the book and I was intrigued by her exploits as well as the many trailblazing female cyclists.

So, I borrow from Karen Lankeshofer’s article about Von Blumen to share her story. Karen has shared a presentation about Von Blumen on YouTube that you can watch if you’d like to know more.

Pioneering female athlete Elsa Von Blumen was a professional bike racer in the 1880s. Her real name was Caroline Kiner and later Caroline Roosevelt after she married Isaac Roosevelt. She also had a brief early marriage to Emery E. Beardsley who was granted a divorce.

Born in Kansas on 6 October 1859, she began her career in her hometown of Rochester, New York, where she started competing as a ‘pedestrienne’ in the very popular sport of race-walking. (as a strange aside one of my great grandfathers John Davidson was born in Scotland just four days after Von Blumen which helps place her in context for me ie. she lived a long time ago, and he died two years after her in Melbourne, Australia).

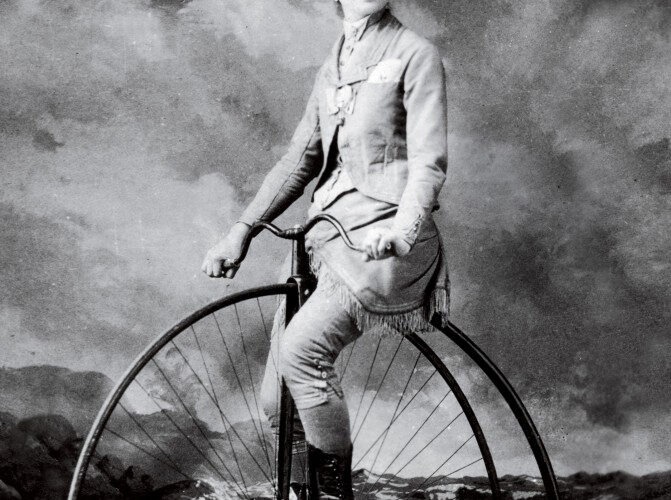

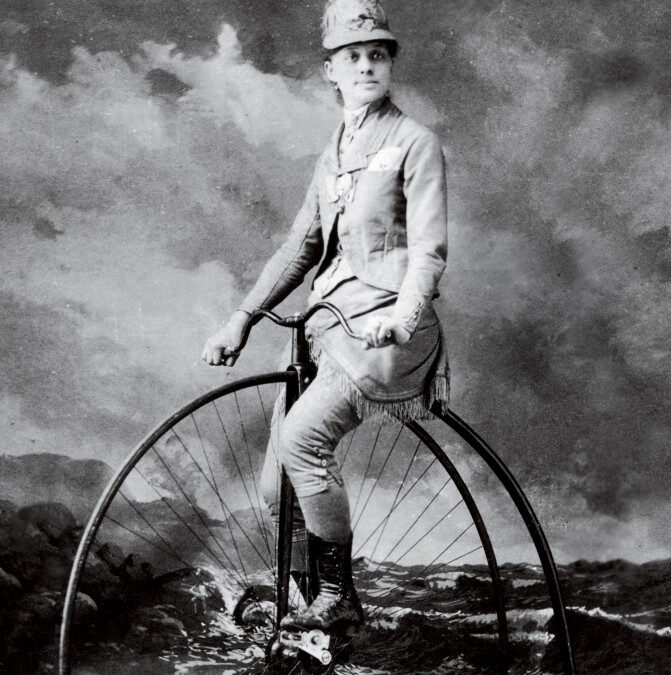

With the encouragement of bicycle manufacturer Colonel Albert Pope (Columbia bicycles), Von Blumen learned to ride a high-wheel bike also known as the Penny-farthing and started competing in 1881.

After giving riding exhibitions, her first race was on 24 May 1881, at Driving Park in Rochester, New York. She raced on a dirt track against trotting and pacing horses and won two out of three heats against each horse. She was a novelty and her manager, Burt Miller (real name was William H. Roosevelt), helped her parlay that novelty into a career of racing that lasted for a decade.

She travelled widely throughout the US racing at county fairs against horses. Eventually, she started arranging competitions, against men and the few other women, who were brave enough to take up the sport of cycling.

She was careful to present herself as a God-fearing, wholesome woman to draw a ‘refined’ crowd to her races. (The races at that time had a deserved repetition of being an excuse to gamble.) She was also very careful to dress in ‘appropriate, decent’ costumes (although she did wear a type of knickerbocker to facilitate riding) to ensure that she appeared respectable to her audience.

Generally, she received very favourable press from local newspapers and their enamoured young reporters, praising her for her ‘pluck’. She was certainly not without controversy, however, and had detractors who did not approve of her lifestyle.

It was also not uncommon for men to run onto the track and hinder her during her races. She suffered several serious falls but always managed to mount her Penny-farthing again and persevere to the finish line.

Her last big race was a six-day event in Madison Square Garden in February 1889 against 12 other female competitors. She came in second even though a spectator stuck his walking stick into her spokes, causing her to fall. Until the end of 1889, she travelled with a troupe of other performers including female cyclist Josie Hawkes, against whom she had raced.

Especially interesting was the attitude the League of American Wheelmen (LAW), the forerunner of the League of American Bicyclists, took toward her. Members of the LAW were required to be amateurs although the organization took it upon itself to govern all bicycle races at that time. Several gentlemen who rode on the same track as Elsa were denied membership in the LAW because they determined they were “professionals”, even if they had only accompanied Elsa around the track for a few laps and took no money for their efforts. The LAW considered her a thorn in its side.

She declared herself not a friend of the new safety bikes which were becoming very popular towards the end of the 1880s, married and retired to Rochester, where she died on June 3, 1935.

I think it’s a real pity she didn’t keep riding but fairly typical of women in that era who usually gave up their adventures after marriage, and definitely after children. She had a son named Claude in 1893.