You need easy gears on your bike to climb hills

One thing that really bugs me about road cycling is there is often an emphasis on being tough, like riding with hard rather than easy gears on your bike, and being eager to ride up long or steep climbs. I’d like to put it on record that I choose to ride with easy gears on my road bike and I choose to avoid very long and very steep climbs. I do accept that as a Sydney-dwelling road cyclist I need to ride up hills but I don’t seek them out. I ride them because I have no choice.

It also bugs me that male riders often focus on the technical mumbo jumbo of riding, and women choose to follow their feelings about bikes. I actually don’t enjoy focusing on the technical stuff either but there are a few things that both women and men should learn about to enjoy their cycling more. One of those key things is understanding their gears, both how to use them properly but also how to choose the right ones for your riding. If you want to know more about how to use them read my previous post, but read on if you want to understand how to choose the ones for you.

There are two key things you need to know more about in order to make your road bike gears easier, and by easier, I mean gears that will help you ride up whatever hills or slopes you need or want to traverse.

If you find yourself struggling to ascend a hill, and have to zig-zag to stay upright or get off and walk, you might need to rethink your gearing.

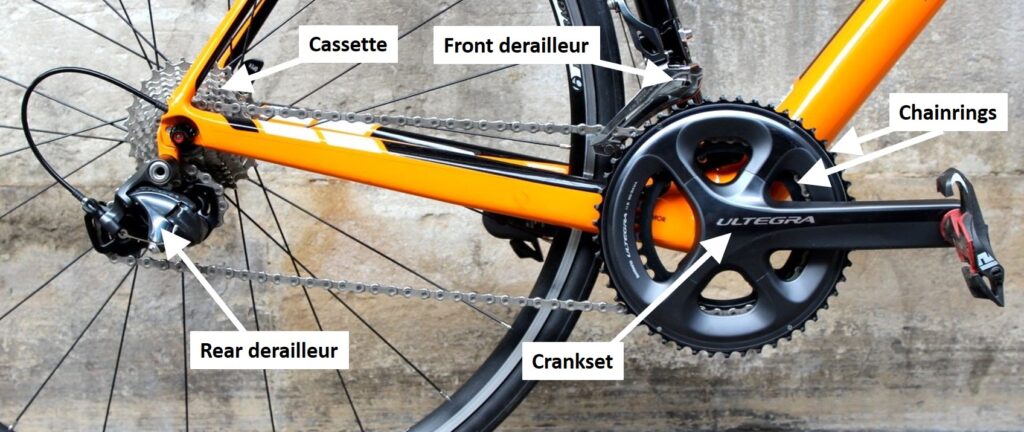

Two principle things come into play – the chainrings that are attached to your cranks (near the pedals), and the cassette which is the thing with all the metal teeth in the middle of your rear wheel.

Most road bikes have two chainrings on the front with a certain number of teeth. When you wheel your new road bike out of the shop and it has Shimano gearing it is likely to have either what is called compact chainrings – 50 teeth of the larger ring and 34 on the smaller, or semi-compact which has 52 teeth on the large, and 36 on the smaller. The smaller the number of teeth the easier it is to ride so I choose 50/34 on my bikes, and I’d recommend it to any rider who wants to get up hills with ease.

The larger chainring gives you bigger, harder to turn gears that move you further per pedal revolution so it’s suitable for higher speeds, while the smaller chainring gives you gears that are easier to turn but move you a shorter distance per pedal revolution so it’s suitable for lower speeds, including riding uphill.

Now to the cassette on your rear wheel where the gear ratios work out the opposite of on your chainrings. In other words, smaller cogs (fewer teeth) on the rear correspond to you harder pedalling, and bigger cogs (more teeth) correspond to the easier pedalling.

The most popular Shimano cassettes have 11 teeth on the smallest ring and anywhere from 25 to 34 on the largest, with 34 being the easiest one. Older riders will tell you they used to have only 21 teeth on their largest ring and that combined with a steel frame and large front chainrings made it really, really hard to get up hills. Thankfully the modern-day bike designers have changed their philosophy making road cycling more accessible.

In an ideal world, both chainrings and cassettes would be easily swapped out but it’s not that easy. Some front chainrings can be changed like the most recent versions of Shimano chainrings can be easily changed but older models are not always that easy. So if you want to move to compact from bigger gearing you might just need to change the individual chainrings which are really affordable or you might have to replace the whole crankset which is more expensive.

The same thing applies to rear cassettes. For some gearing, it’s as simple as replacing the cassette but with others, you need to replace the rear derailleur (the thing that changes the rear gears), and sometimes the chain.

Road bike rear derailleurs often come in “short-cage” and “medium-cage” varieties. Most short-cage rear derailleurs can handle no larger than a 28-tooth cog, while a medium-cage rear derailleur, you can go up to a 34-tooth cog.

Your bike comes equipped with a chain that is long enough to be able to wrap around your largest cog and your largest chainring at the same time. As you shift into smaller cogs and/or chainrings, it’s the job of the rear derailleur to take up that extra “slack” in the chain. How much slack they can handle depends on the length of the “cage,” which is the part of the rear derailleur that hangs down towards the ground.

When I decided to move to an 11-32 rear cassette from an 11-28 to make climbing easier, I had to change my rear derailleur, cassette and chain. This cost me a couple of hundred dollars but to me, it was well worth it. I suggest you head to your favourite local bike shop to ask them for advice on how to make the gears easier on your bike. And if they tell you not to do it, then go to a bike shop that will help.

And if you think I’m alone with my preference for easier gears, you might be surprised to hear that many pro male riders choose the same sort of gear ratios for the big mountain stages of the Tour de France and other hilly races.